The Book Thief: Words, Skies, Childhood, and the Comfort of a Commoner's Story

CONTENT WARNING: Contains spoilers

When Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party took over Germany, they were a minority uncontested by the majority. Still, from only 3% of votes to 18.3% and then 37.3% in 1932, the faction grew its political influence quickly during elections at Reichstag (Germany’s national legislative building). Perhaps it was the Reichstag Fire in 1933 that firmly established Hitler’s presence as dictator of the country – but perhaps it was also his use of words, a tool that if wielded in a certain way, can manipulate thousands of humans. The Nazis exploited the Reichstag Fire by informing the general public of communists planning a violent uprising. Hitler’s words enabled him to easily pass the Reichstag Fire Decree, a law that suspended constitutional rights and permitted his tyrannical rule. But words can also be used for the better: Liesel Meminger used them to comfort family, friends, and Death himself.

Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief describes a peculiar yet inconspicuous German family living in the fictional town of Molching (based on the real town Olching) during the brink of World War II. A likable Hans Hubermann and his not-as-amiable wife Rosa (who has a knack for cursing, especially at the people she loves) adopt nine year old Liesel Meminger and later hide Max Vandenburg, a Jew, in their basement. The family lives in a poor neighborhood relatively untouched by the bloody violence of the ongoing war, and their story is told from the perspective of Death himself, a straight-forward and dead-pan (get it) narrator who sources his material from Liesel’s own memoir. Liesel is The Book Thief who steals stories from others, but reads and writes them for others as well.

Despite the focus on Liesel’s life, Zusak makes it clear that WWII is going on in the background. He underscores the ‘World’ in World War II: no human at that time could live without some connection to the war. For Liesel, it is the Jew in her basement. She was fortunate (or to some, unfortunate) enough to be adopted into a family sympathetic to the persecuted, forming an unlikely friendship with a Jew. Liesel and Max communicate primarily through words – stories – and in order to thank her for her friendship, Max even writes a book for the story-hungry Liesel. Inevitably, he mentions Hitler:

After Hitler “decided that he would rule the world with words… He planted them day and night, and cultivated them. He watched them grow, until eventually, great forests of words had risen throughout Germany… It was a nation of farmed thoughts” (445).

It began with the Nazis’ racial superiority ideology – for instance, among Slavs, the Nazis categorized Slovaks and Croats as superior to Poles and Czechs. Hitler also had an obsession with “Aryan,” the belief that certain groups of the European race, especially those with “beautiful blond hair and big, safe blue eyes” (61), were pure and superior. In particular, Hitler used propaganda to convince not only Germans but also Ukranians, Lithuanians, and other ethnic groups to hate Jewish people up to the point where they would murder Jews without prompting. Through Hitler’s portrayal of minorities as dirty and scheming, he gained if not supporters, then bystanders – who equally allowed his mass murdering to continue.

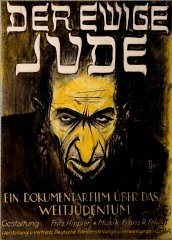

Advertisement for the German antisemitic film, Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew). 1940. Source: US Holocaust Memorial Museum

He “invited people towards his own glorious heart, beckoning them with his finest, ugliest words… And the people came” (445).

In fact, many Jews were brought to their eventual death locations through deception – Jews in Poland were told that only “non-essential and unproductive elements” would be sent to the east for labor. When poorer Jews were deported, others held on to the illusion that they’d be left alone. Although Max and Liesel’s family were not ones to believe the Nazis’ lies, many of the persecuted (which included Poles, LGBTQ+ people, communists, and other minorities along with Jews) couldn’t believe that death camps existed, or that they had arrived at one after being transferred from concentration or forced-labor camps. At the five killing centers in Germany-occupied Poland, over 2,772,000 Jews – only 46% of Jewish victims – were murdered. Still, the masses were misled by the Nazis until the end; the soon-to-be killed were greeted by music bands and gates adorned with cheerful messages, and prisoners were taught to refer to crematories as “bakeries.”

The infamous Auschwitz I concentration camp gate – “arbeit macht frei, work makes you free”. In reality, people who entered Auschwitz would die by the Nazis. Source: The Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

A unique aspect of The Book Thief stems from its surprisingly eloquent and contemplative narrator: Death. An avid enjoyer of skies, today he might be a big enjoyer of sunsets, but in this story, “the sky [is] the color of Jews” (349). Death describes his experience in former Stalingrad, Russia:

In 1942 and early '43, in that city, the sky was bleached bedsheet-white each morning.

All day long, as I carried the souls across it, that sheet was splashed with blood, until it was full and bulging to the earth.

In the evening, it would be wrung out and bleached again, ready for the next dawn.

When he later travels to Mauthausen, one of over 44,000 Nazi camps, Death picks up souls at a great cliff, some at the bottom, some still falling – “there were broken bodies and dead, sweet hearts. Still, it was better than the gas” (349). He pleads the reader for understanding, asking to “please believe me when I tell you I picked up each soul… as if it were newly born” (350) albeit even he becomes tired, unable to keep track of all the souls he has collected. When Death looks to the sky for a distraction from the atrocities he has witnessed, he notices that “even the clouds were trying to get away” (350). Zusak’s visual representation of Earth during WWII, as well as his personification of death, depict a human world so deep in self-destruction that even Death is more empathetic than Germany’s primary perpetrator.

Now, the main character of this novel is Liesel, and Zusak continuously reminds readers of her youth through her hope and happiness. The Book Thief depicts a nuance that is present in both WWII and every other conflict: not everyone on the enemy side is an enemy. Liesel, a German girl, is relieved and ecstatic when Max – a Jew – recovers from a cold. For Liesel and her friend Rudy, who lives in the same poor neighborhood, a penny on the street – enough for only a singular piece of candy – is enough for the day to be “a great one, and Nazi Germany was a wondrous place” (156). The duo embarks on food-stealing adventures because of their hunger, a result of the increased food rationing that prioritized ‘heavy workers’ and ‘normal consumers’ who played a more significant role in war. Liesel’s experience demonstrates the harsh reality of German children during WWII: they were sent to the Hitler Youth to idolize fascism, Hitler, and book burning, while living in terribly poor conditions. Born into an era where their kind is deemed the enemy, German children like Liesel are overlooked and grouped with the Nazis – despite Liesel herself witnessing her father get unwillingly drafted in the army in 1942. Liesel’s innocence suffers especially when her neighborhood gathers in a basement during bomb alerts; there, she is the one who, with her books, reads to calm others down. At this point, although “the book thief saw only the mechanics of the words – their bodies stranded on the paper, beaten down for her to walk on” (381), she successfully keeps the others’ minds busy. One day, accompanied by Rudy, Liesel even watches an Ally airplane crash to the ground with its owner dead. Her childhood is cut short by a war that she did not choose to be in.

Max, who is fairly young himself, faces a similar decline in naivety first when his father dies during WWI. It is Hans who tells him that he was not foolish: “you were a boy” (219). Max is later overcome by guilt, as he understands that his presence in the Hubermanns’ basement endangers them. At only 22, Max realized that “Living was living. The price was guilt and shame” (208).

Ultimately, The Book Thief tells us that war is never black and white. Many families were unfooled by Hitler’s words; for instance, Rudy’s father Alex Steiner was a Nazi but “did not hate the Jews, or anyone else for that matter… Secretly, though, he couldn’t help feeling a percentage of relief (or worse–gladness!) when Jewish shop owners were put out of business – propaganda informed him that it was only a matter of time before a plague of Jewish tailors showed up and stole his customers” (59). Steiner makes the logical decision to support his family above all else, prioritizing their financial stability. “Somewhere, far down, there was an itch in his heart, but he made it a point not to scratch it” (60).

As for Hans Hubermann, he was saved by a Jew during WWI. While in the army, Hans “ran in the middle, climbed in the middle, and he could shoot straight enough so as not to affront his superiors. Nor did he excel enough to be one of the first chosen to run straight at [Death]” (174). He was the only person from his unit to survive, and when he also found his way back home after being drafted for WWII, it became clear that his goal was to survive – not pick a side. Still, Rudy, whose father was also drafted, asks himself “Why Hans Hubermann and not Alex Steiner?” (480). War can turn one against alleged friends, because amidst the bigger picture, each individual only wants the best for themselves and their loved ones.

Ultimately, The Book Thief is a testimony for the thousands of civilians that suffered during World War II. In the novel, each family deals with less and less food over the years: when Max becomes sick, Liesel’s family secretly appreciates the extra food on their plates. The end of the novel describes a situation that can only be blamed on the Allies; although the Germans may be the perpetrators, the Allies bomb Liesel’s loved ones. In Liesel’s neighborhood, one German man helplessly watches his brother die, and then “[kills] himself for wanting to live” (503). German citizens are hit by desperation, and yet, it is this very fact that humanizes them and prevents their vilification. This is the comfort that a commoner brings: the comfort of knowing that not all people are inherently bad, and that every individual has their own story to tell. The Book Thief undeniably shows that WWII was a disaster for everyone involved, no matter which perspective we choose to take. Hitler used words to abuse, but it is the words coming from each person’s mouth that give us the full picture of WWII. Liesel ends her autobiography recognizing this: “I have hated the words and I have loved them, and I hope I have made them right” (528).

Sources:

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/defining-the-enemy?series=1

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-reichstag-fire

https://www.britannica.com/place/Germany/World-War-II , https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/world-war-ii-history

https://www.yadvashem.org/holocaust/about/final-solution/deportation.html

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/nazi-camps

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iQeDvnapdlg

by VICTORIA WOO

Views expressed above represent the opinion of the author and are not intended to represent Lexspects editorial staff or Lexington High School.