What is Land Day?

Note: The naming conventions for this article draw on the framework set out in this essay by the Palestinian writer Mary Turfah, whose grandfather was expelled from the village of Salha (صَلْحَة) during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. As the latter drew to a close in late October, Israeli forces summarily executed 105 Palestinian civilians in Salha before deporting the survivors to southern Lebanon (where their descendants are still trapped to this day). Shortly thereafter, two Jewish settlements were built on the lands of Salha, both of which—in light of their sordid origins—I will be enclosing in scare quotes: “Yir’on” and “Avivim.” This choice has been replicated for all other Hebrew place-names in Palestine except where otherwise deemed inappropriate.

Every March 30th, Palestinians from around the world link arms to commemorate Land Day. But what is the significance of this date anyway, and why is it such a potent symbol of the struggle for Palestinian freedom? To answer both of these questions, a brief foray into the historical record is necessary.

The principal subject of the first Land Day was not in fact the Palestinian refugees (i.e. those residing in Gaza and the West Bank) but rather their counterparts within Israel itself. These Palestinians, otherwise known as the ‘48 Palestinians (so called because they had managed to evade being ethnically cleansed from the landmass of what became Israel during the 1948 war), initially presented something of a quagmire for the Zionist leadership. For though they held legal title to roughly a quarter million acres of coveted land, their status as Israeli citizens seemed to foreclose the prospect of simply extinguishing this title so that the land in question could be handed over to Jews, as had been done with the Palestinian refugees. In the case of the latter, Israeli lawyers revived an archaic British legal code whereby the property of any person(s) classified as “absentee” (read: ethnically cleansed) was rendered ownerless and thus free for the taking. The result: virtually overnight, almost 80% of Palestine was stolen, including 25,000 buildings, 10,000 shops, and 60% of all arable land. To seal the deal, IDF death squads killed and maimed upwards of thousands of Palestinian refugees in a bid to deter them from returning home. In the event, their efforts paid world-making dividends: from 1948-1953, over 94% of new Jewish settlements in Israel were built on confiscated Arab property.

As for the ‘48 Palestinians, the Rights of Man proved to be no match for Zionism’s Orwellian prowess. Knowing full well that these Palestinians were not “absent” from their homeland but in fact very much present, the Israeli government branded them with a novel appellation designed specifically to expedite the process of their removal: “present-absentee.” What exactly this status meant varied by scenario. In some cases, it could denote a person who had fled their village to escape combat even if they never exited Jewish-held territory at any point during the war. In others, it was deployed to retroactively punish such “crimes” as vacating one’s residence to seek refuge in a building located mere meters away. In yet more, the target need not have even moved a single inch so long as their eviction enjoyed the rubber stamp of a nameless bureaucrat. In any event, unless a ‘48 Palestinian could prove beyond a reasonable doubt that they had remained stationary to a system which was genetically bent on their erasure, nothing was off limits: there was a nation to be fed, and the nation-builders took no prisoners.

Figure 1: Renowned ‘48 Palestinian poet and author Mahmoud Darwish, who along with his family was uprooted from the Palestinian village of Al-Birwa (البروة) during the Nakba. Much of Birwa would later be demolished by the Israeli army, save for a lone cemetery which is now controlled by two Jewish agricultural colonies, “Yasur” and “Achihud.”

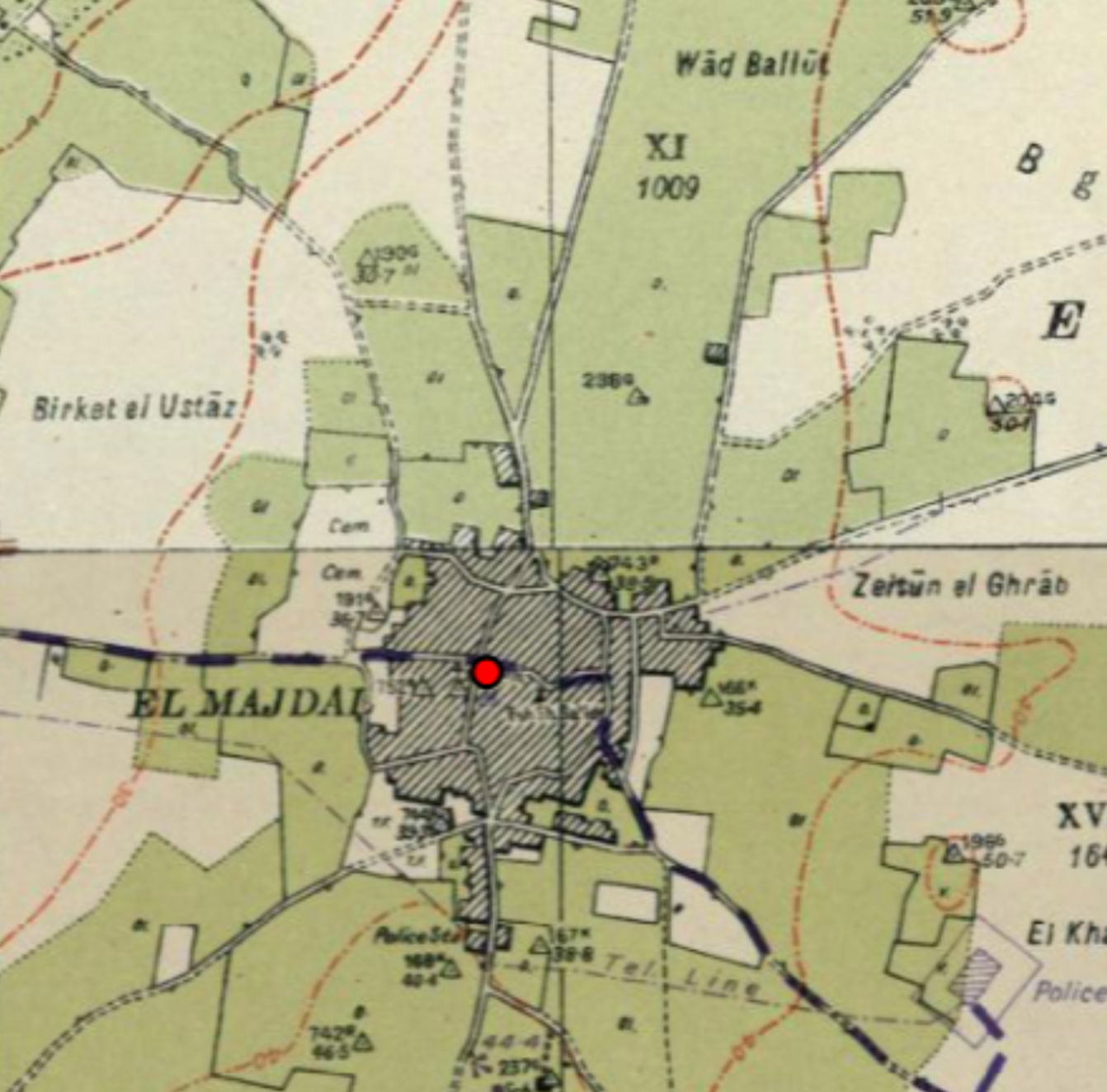

Figure 2: Map of the former Palestinian village of Al-Majdal (مجدل). During the Nakba, most of Majdal’s inhabitants fled in response to Jewish attacks, with much of the minority who stayed behind later being expelled to Gaza. The new Jewish-only town that was built on its ruins, “Ashkelon,” recently made global headlines as it was one of many settlements targeted by Hamas in its October 7 military operation.

Like their exiled brethren, however, the ‘48 Palestinians refused to go quietly, and such a temperament was no good for an enterprise that had vowed from Day 1 to turn Palestine into a land free from non-Jews. To this end, from 1948 to 1966 every Palestinian in Israel was placed under strict martial law (citizen or not). The dual purpose of this regime—whose operation later furnished the blueprint for Israeli rule over Gaza and the West Bank—was to confine ‘48 Palestinians to the lowest rungs of the Israeli labor market while also preventing them from reclaiming the very spaces from which they had been expelled mere weeks or even days ago. Achievement of both sometimes involved the Israeli military arbitrarily declaring huge stretches of (overwhelmingly Arab) farmland closed areas, whereupon the Minister of Agriculture would punish Palestinians who had “neglected” to recultivate their fields by confiscating them entirely. In virtually all cases, the plots concerned were swallowed up by neighboring Jewish settlements. On the other hand, control over time frequently proved no less exacting than control over space, as exemplified by the 1956 Kafr Qasim (كفر قاسم) massacre in which 49 Palestinian civilians were slain by Israeli police for breaching a curfew order whose existence they hadn’t even been aware of.

Figure 3: Barbed wire marks the limits of a ghetto designated for Palestinian inhabitants of Jaffa, an Arab city depopulated by Israeli forces in 1948.

Yet not even this could sate the appetites of Palestine’s neo-conquistadors. Indeed, by the mid-1970s the latter had actually begun to ratchet up their efforts, with one Israeli parliamentarian declaring with alarm, “As it is, alien elements [‘48 Palestinians] take over the lands of the state. National land is robbed by others. Soon Jews will have no place to settle in.” Readers familiar with my study “The modus operandi of the Jewish state” will here recall the infamous Koenig memorandum, in which Northern district commissioner Yisrael Koenig advocated to renew “Judaization” (read: ethnic cleansing) in the last corner of Israel with an Arab majority, Galilee. Accordingly, shortly after the Six-Day War, a newly emboldened settler vanguard accelerated the conquest of northern Palestine, with one of their ventures including, grotesquely enough, an attempt to confiscate 740 acres of land from Kafr Qasim in late 1975. In response, ‘48 Palestinian politicians, activists, lawyers, and intellectuals from across the country mobilized to establish the National Committee for the Defense of Arab Lands in Israel. The committee in turn set up local branches in each Palestinian town or village threatened by Judaization, with particular attention devoted to Sakhnin (سخنين), Arraba (عرّابة), and Deir Hanna (دير حنا). But the real showdown was yet to come.

On February 29, 1976, the Israeli government announced a plan to expropriate 4,900 acres of Palestinian land in the Galilee for Jewish settlement. A week later, the committee convened a meeting in Nazareth during which it was decided “to hold a general strike on 30 March 1976, and to declare this day to be Land Day in Israel.” And so they did. Starting in the aforenoted triangle of Sakhnin, Arraba, and Deir Hanna, Arab Palestine thus launched its greatest anti-colonial revolt since 1936, distinguished this time around by the blockade of roads as a means to preempt a Zionist counteroffensive. Yet just as their British shepherds had 40 years earlier, Israeli Jews did not stand idle as their palace came under attack. In a dark portent of next decade’s intifada, Israeli authorities deployed a nationwide armada of police, army units, and border guards to quell the uprising in its tracks. Village after village was so raided, as an all-engulfing torrent of batons and live fire descended over each and every one of the Jewish state’s non-Jewish subjects. By the time the carnage ceased, six ‘48 Palestinians had been killed (half of them women), with hundreds more having been wounded and/or arrested.

Figure 4: A Palestinian child in Gaza holds a sign to mark the 33rd anniversary of Land Day (translation: “Palestine is one”).

Though seldom acknowledged by non-Palestinians today, the history of Land Day can nonetheless augment our understanding of the conflict significantly, if only by reminding us what it’s about in the first place: land. Indeed, armed resistance to Jewish colonization in Palestine didn’t even begin in earnest until the 1910 Al-Fula (العفولة) affair, in which an Arab village by the same name faced the threat (and eventual reality) of expulsion to make way for Jewish settlers. Likewise, the aforementioned 1936-39 revolt was itself preceded by the forced urbanization of large swathes of Palestine’s Arab peasantry, or fellahin (فلاحين), due in large part (though not wholly) to Zionist land grabs. A decade later, the shock of the Nakba would multiply this effect a thousandfold, thereby etching into the Palestinian collective psyche a profound sense of loss which has proven stubbornly difficult to extinguish. On the contrary, Israel has done almost everything in its ability to amplify it, whether by circumscribing Palestinians’ access to the spaces they hold dear or further snatching up what little they have left.

Far from religious extremism, it is thus the question of place which has given the Palestinian freedom struggle its thrust for the past century. And never before has the question of place been more urgent than during Israel’s ongoing Holocaust in Gaza. With close to 90% of the strip’s population having been displaced and large swathes of its civilian infrastructure annihilated, it is beyond manifest that any plan for rehousing the Palestinians of Gaza must necessarily depart from the status quo ante. In this spirit, I propose the following course of action: let the Palestinians who elect to stay behind remain in place and give the rest the option to reclaim their stolen homes in southern Israel (the fate of the Israelis “whose” property would be appropriated can be determined at a later date). Not only would this exact a worthy price from a population engaged in what could very well end up being the greatest crime of the 21st century, it would also obviate Gazans’ principal motive for employing violence against their colonizers in the first place, i.e. unlawful obstruction of access to their homeland. From here, similar initiatives could be launched across the West Bank and Galilee, perhaps even encompassing the very tracts whose confiscation precipitated the events of Land Day (already likely to have been evacuated as a result of Hezbollah rocketfire). Whatever the case, unless and until the Crusaders are forced to cough up so much as a fraction of their accumulated loot, they will forever be sitting on a regional timebomb. And if/when the latter detonates a second time, they will once again have no one to blame but themselves.

If you’re interested in further elaboration of this article’s themes, consider reading this interview I conducted with a Palestinian student at LHS last December.

For a comprehensive timeline of the evolution of Palestine’s land regime—as well as how this regime eventually came to be weaponized against the Palestinians—see here.

Finally, if you’re willing and able to support the people of Gaza during their most urgent hour of need yet, please consider donating to any of the following organizations:

Palestine Children’s Relief Fund

Palestine Red Crescent Society

United Nations Relief and Works Agency

BY NEO CHATTERJEE